Early Modern Women's Marginalia

The Library of Libraries

Attribution

A Definition of Graffiti:

The database uses the term graffiti for a range of marks that are primarily visual in nature, consisting of images, pasted material, object traces, letter practice, doodles, smudges and stains.

RCIN 1051956 Psaultier de David, Royal Collection Trust, Windsor Castle Royal Library, Windsor

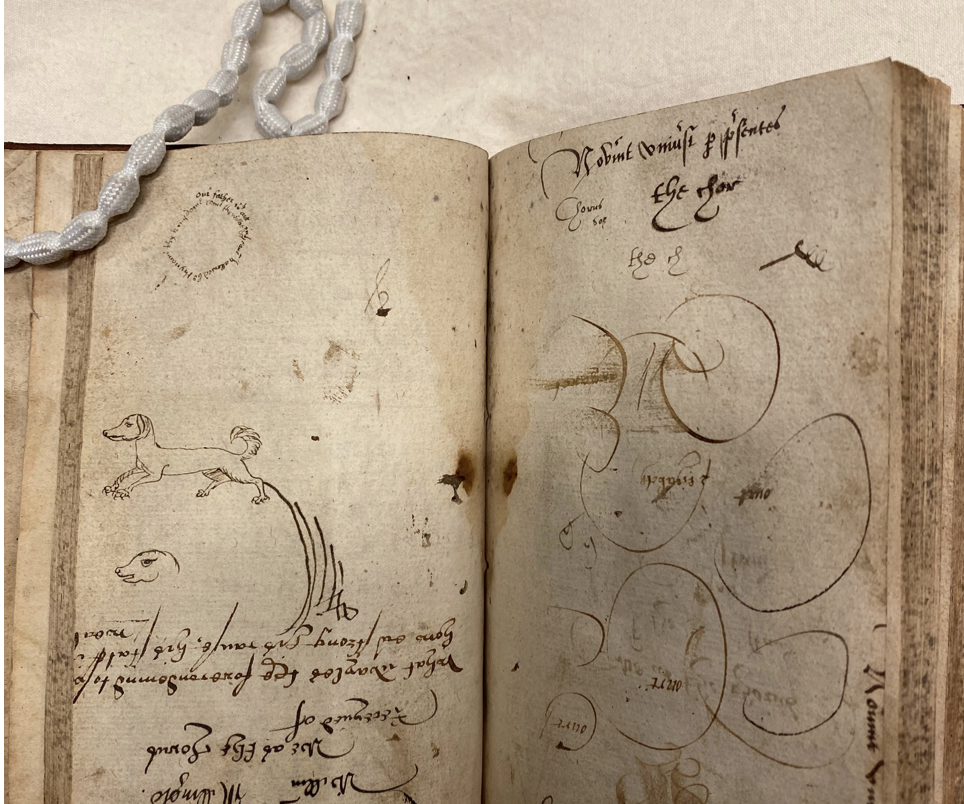

Figure 1, from Marcello Palnigenio Stellato's The zodiake of life (London, 1565), Bodleian Library, Douce P 584, sigs. N7r (left), B7r (right top), and E4v (right bottom).

Most scholarship on early modern women’s marginalia to date has concentrated on its verbal forms, yet women’s annotations also include visual marks or images of varying degrees of legibility and complexity, ranging from stars and manicules, doodles, copies of typographical ornaments, drawings in pen and ink, and the insertion of images into texts through cutting and pasting. These visual forms, which we have grouped under the term ‘graffiti’, comprise an exciting and largely unexamined sub-corpus within early modern women’s marginalia, providing new evidence of how women read, how they saw their world, and how they used their books. Graffiti also illuminate how women engaged with formal categories of visual expression such as calligraphy, copying and drawing, with implications for our understanding of their education and their relationship to humanism. The collection of graffiti found in our database show how important both texts and images were to the ways in which women perceived and represented their worlds.

Visualisations of types of marginalia in the database, with graffiti as a percentage against ownership, annotation, and recording.

Visualisations of types of marginalia in the database, with graffiti as a percentage against ownership, annotation, and recording.

One important use of image in the margins has been to help readers note and highlight a feature of a text, allowing it to be more easily understood and remembered. Images such as stars and manicules (hands pointing to certain lines) are the most common forms of such visual marginalia, and they add the humanist concept of enargeia (vividness) to a reader’s interaction with the page, amplifying, decorating and ‘colouring-in’ texts not only with marks such as underlining but with images drawn from what the reader saw in the world around them. Women as well as men annotated their texts using such visual aids, as Mary Powntis’s manicules in a copy of The Zodiake of Life show. There are very few examples of women’s use of this kind of visual annotation, but they do exist, showing that women had access to elements of humanist annotation despite their exclusion from the all-male humanist schoolroom. Rather than strict segregation, women’s use of forms such as the manicule to annotate texts and to mark passages show how the education of men and women overlapped. Women as students and teachers can be found at the sixteenth-century schoolroom’s edges, and their levels of literacy and education increased throughout the seventeenth century.

Some women, especially royalty, did receive a humanist education which included instruction in writing, drawing, painting, perspective and geometry. Again, we have very few traces of how royal women acquired and used these skills. One stunning exception is the drawing of an armillary sphere that faces a quatrain by the princess Elizabeth on the final pages of a Book of Hours, where a scroll beneath the image in Elizabeth’s distinctive italic hand contains a line from Petrarch’s Triumph of Death: ‘Miser é chi spemé in cosa mortal pone’ (Wretched is he who places hope in a mortal thing). It is impossible to know if Elizabeth drew this image or not, but her inscription means that across the opening image and text work together; the quatrain and its signature adhere to the armillary sphere, the book upon which it rests, and the line from Petrarch in Elizabeth’s hand. This is a collection of visual and verbal annotation to be circulated, a way in which the princess Elizabeth could signal her piety, her desire to be guided by the word of god rather than earthly things, as well as her spirited aversion to the damaging workings of the ‘inward suspicious minde’.

Emmerson Collection State Library Victoria, Melbourne, RAREEMM 322/21, Samuel Daniel, Certaine Poems (London, on blank leaves inserted after sig. F6v)

Emmerson Collection State Library Victoria, Melbourne, RAREEMM 322/21, Samuel Daniel, Certaine Poems (London, on blank leaves inserted after sig. F6v)

However, the majority of graffiti that we have attributed to women in the database take very different forms to these polished examples. On the title page of a 1623 copy of the Arcadia held in the Bodleian library, the half-cropped signature of Elizabeth Duke is accompanied by a set of marks that include looping lines, dashes, and blots. This kind of inchoate mark is very commonly encountered, especially on flyleaves, endpages, paste downs and title pages. Often appearing as scribble, closer inspection can reveal women’s names, accompanied by letter practice and pen trials, as well as doodles. While such doodles can often seem to indicate inattention, often they constitute the shape-forming that was a building block of learning to write, or they take their cues from the visual world of the book, copying typography, ornaments or images from its pages. Sometimes a cluster of marks contains all of these elements as well as what may be original drawing. In a copy of Samuel Daniel’s Certaine Poems, we can see the name of Elizabeth Court, surrounded by swooping circles that were a form of letter practice, as well as a circular inscription of the Lord’s Prayer in Court’s hand, and partial and complete drawings of a dog, less easy to attribute.

Around 7% of our database comprises graffiti, but images are far more difficult to attribute to women agents than textual marginalia, where hands can be matched. When a volume has a single woman marginalist, images can be attributed to that woman as probable; but far more commonly images and doodles appear on pages with multiple hands and can only be attributed as possible through proximity or the incorporation of textual elements. Object traces, smudges and stains, while no doubt caused by women users and readers of books, are almost impossible to attribute. So while we can trace graffiti to women only occasionally, it is likely that women contributed in far greater numbers to the pages of pen trials, letter practice, doodles and drawing than we can demonstrate.